Left Unfinished: Why state law makes it hard for homeowners to hold builders accountable

MONUMENT, Colo. (KRDO) - Homeowners throughout southern Colorado paid hundreds of thousands for custom homes, only for the projects to be abandoned. To add insult to injury, those affected learned laws in Colorado do little to help get their money back.

Roger and Sandra Ewer stand in front of what was supposed to be their dream home. On more than two acres of land in Monument, right next door to their best friend, the Ewer’s said it was perfect for their family of five boys.

“We were fortunate enough to find a house that was large enough for our family, kind of around the corner here in Monument from where we were renting,” Roger Ewer said.

The house stands naked though, scaffolding still guards half-completed walls. The back deck slumps after years of neglect. It looks as if it’s still being constructed, but the Ewers know their dream home is just that - a dream.

“I don't think that you can total what was lost in the dream,” Sandra Ewer said.

The Ewers entered into an agreement with Craftsman Homes and Interiors in 2020, which included a $50,000 down payment. The company was owned by Colorado Springs couple Dwight and Joni Mulberry.

The two now work at Lewis-Palmer High School. According to administration, Dwight is a part-time industrial technology teacher, while Joni is the bookkeeper for the school. According to the Colorado Secretary of State, the Mulberrys started Craftsman Homes and Interiors back in 2017.

For years, it was reputable. Many homeowners actually picked Craftsman Homes because of a referral from a previous customer. However, those that hired Craftsman Homes in 2019 or later reported work wasn’t what they expected.

After the Ewer’s signed their contract, they said work was slow and excuses were quick. They said it took nearly a year for the foundation to be poured.

“Every lie sort of compounded to a point where you just never trusted anything that was said,” Roger said.

Most of the communication with the Mulberrys was through an online portal.

“There is documentation in the construct portal of all the frustration and aggravation and essentially us begging for information,” Roger said.

“Please understand that we are approaching the 2 year mark and I cannot begin to express how much this process has taken from us emotionally and financially,” Sandra Ewer wrote to the Mulberry’s in May 2022. “We just need to see it done so we can move on with our lives.”

Over time, the walls of their house were put up, but all work on their property stopped in 2022. The Ewers were out $150,000 with no house to show for it. Any communication with the Mulberrys also ended when the Ewers said they were kicked out of the portal.

In January 2023, the Ewers filed a lawsuit against Craftsman Homes and the Mulberrys, accusing them of fraud, concealment, misrepresentation, and theft. Two months later, the Ewers realized they weren’t the only ones with the same accusations.

In March, the Mulberrys’ filed for bankruptcy, listing more than 170 creditors and totaling at least $2.1 million.

“Our story’s sad, but their stories are worse,” Roger said. “People were robbed all across Colorado."

About 35 miles southwest, Doug and Lucinda McIver also filed a lawsuit after experiencing a similar problem to their custom home in Woodland Park.

“It was an elaborate pattern of deception,” Doug McIver explained.

The McIvers said they signed a contract with Craftsman Homes and Interiors in February 2021. Their plan was to build their retirement home on a quiet lot in northern Woodland Park on the edge of a small lake.

Like the Ewers, the McIvers said progress was slow. It wasn’t until Rusin Concrete, a subcontractor, placed a lien on their property in the summer of 2022 that the McIvers knew something was wrong.

A lien is a claim or charge on a property to ensure payment of a debt, obligation, or duty to the lender.

Rusin Concrete claimed they weren’t paid for pouring the foundation of the house. Dozens of other subcontractors soon made the same allegations.

Jim Brinkman, the owner of Crossed Paths Surveying, also placed a lien on a Craftsman Homes property, because he said the company owes him $55,000 for subcontractor work.

“Paychecks were slow to come — a lot of convincing and reminding,” Brinkman said. “Then pretty much it became excuse after excuse.”

On other projects, the Mulberrys are accused of taking money and not doing any work.

Scott and Carolyn Sant Angelo live in Florida but paid Craftsman Homes nearly $250,000 to build a vacation home in Breckenridge. Two years after signing a contract, the lot sits completely empty.

Mark and Brenda Peterson paid a $25,000 down payment and entered into a contract with Craftsman Homes and Interiors in 2021 for a house in northern Elizabeth. A year later, they said the Mulberrys abandoned the project.

“I think they chose at one point to work with us, knowing that they needed money to pay other people,” Mark Peterson said. “They took our money and then they did nothing.”

The Mulberrys and their attorney declined to talk to 13 Investigates about the numerous lawsuits against them. But in court documents, the couple denies the allegations.

They claim the homeowners have no proof that they intended to breach a contract or steal money.

“The Petersons then use unsupported legal conclusions to attempt to turn an alleged breach of contract into fraud, theft, and an intentional injury,” the Mulberry’s said in a response to the Peterson’s lawsuit.

“It feels like fraud to me,” Mark said when asked about the Mulberry’s legal response. “They took money that was supposed to go to our project and they used it for something else.”

Despite the numerous people out money, 13 Investigates learned Colorado law leaves people in these situations with few options.

While homeowners believe they were a victim of a criminal act, law enforcement more often than not points them in the direction of civil attorneys, like David Hannum at Robinson and Henry.

“We see a situation where the police aren't willing to prosecute it because they say, ‘Well, that's like a breach of contract. You just didn't perform on the contract.’ I don't see it that way,” Hannum said. “I see you stole nearly $25,000.”

Hannum said Colorado’s contractor fraud laws are behind other states.

In Tennessee, it’s a crime for a contractor to fraudulently breach a contract or not work on a project 90 days after getting paid. This is called a “time is of the essence clause.” Louisiana has a similar law but with an even shorter deadline of 45 days.

Colorado doesn’t have a criminal law for breach of contract or work deadlines, but the state does have the Construction Trust Fund Statute, which imposes penalties on anyone who uses construction funds for any purpose other than the job that money was intended for. If violated, the person could face fines, probation, or jail time for felony theft.

Still, homeowners are typically advised to just file a civil lawsuit.

“People are getting victimized out there and those crimes aren't getting prosecuted,” Hannum said.

According to the 4th Judicial District Attorney’s Office, 71 contractor fraud cases have been filed since 2018. Of those, 40 were resolved — nearly all of them felony convictions. It took nearly a year for those cases to be prosecuted once they were filed and included an average prison sentence of 4 years and an average restitution of $76,000.

According to Colorado’s law books, criminal theft is intentionally depriving another person of money by threat or deception. The McIver’s, who now have to sell their half-finished Woodland Park property, said they can prove that’s what happened to them.

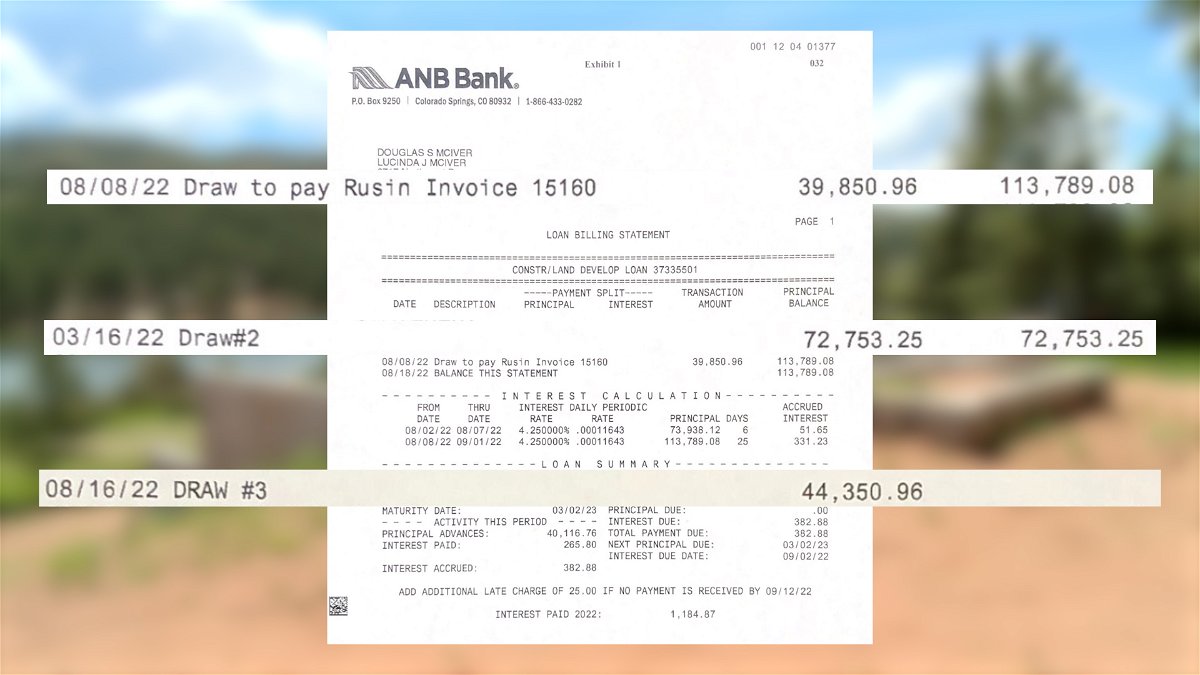

To pay for their new home, the McIvers took out a construction loan. Anytime the Mulberrys needed money to pay a subcontractor or buy materials, they requested a draw. These draws outlined how the money would be spent and had to be approved by the McIvers.

When the lien was placed on their property by Rusin Concrete because they weren’t paid for pouring the foundation, the McIvers called other subcontractors. According to the loan draws the Mulberrys took out, a number of subcontractors were supposed to be paid. But The McIver’s said every subcontractor said they didn't receive a cent.

“It wasn't until it became obvious about a year ago that they had misappropriated about $130,000,” Doug said.

“It's almost like a Ponzi scheme in the sense that instead of investors, you have clients and you're taking money from current clients and you're paying back past debt,” he said.

However, this proof is somewhat irrelevant to their civil lawsuit. Since the Mulberrys filed bankruptcy in March, all civil lawsuits against them are now on hold.

“If you can defraud people of hundreds of thousands of dollars and then simply kind of throw your hands up and file bankruptcy, then the legal system says, ‘Well, we don't have anything,’” Doug said.

The McIver’s attorney, Taylor Minshall, is now advising them to drop the lawsuit, he told 13 Investigates. He said because the Mulberrys have so few assets and so many creditors listed against them, any returned money would be minimal and far less than the cost of attorney fees.

“We've lost all this money and our system is supposed to make us whole, but we can't even get there,” Minshall said. “Now we have to spend all this extra money to go after them, and then there's a chance we might not recover it all. That's the sad reality.”

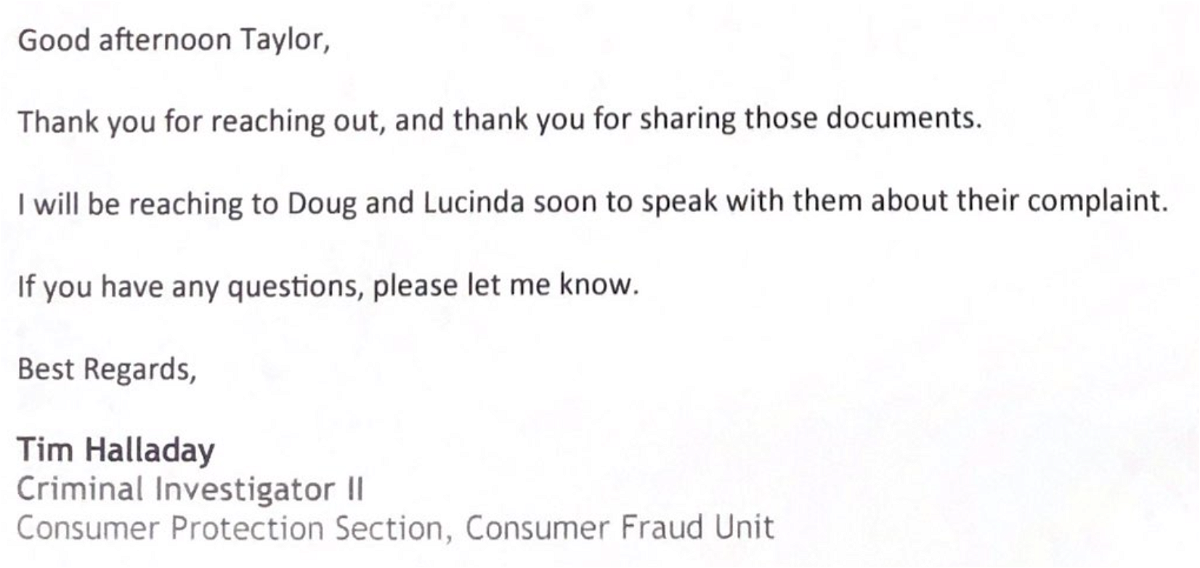

13 Investigates obtained emails between the Colorado Attorney General’s Office and homeowners about an investigation into Craftsman Homes and the Mulberrys.

13 Investigates reached out to the AG’s Office, but they wouldn’t confirm the investigation or if it was for criminal charges.

With little help from local law enforcement and the court system, the AG’s investigation is the only justice these homeowners can now afford.

“This was our dream,” Lucinda said. “This was our retirement. This is what we've planned for over 20 years. Now it’s gone.”