Shortage of doctors leaves patients waiting for answers

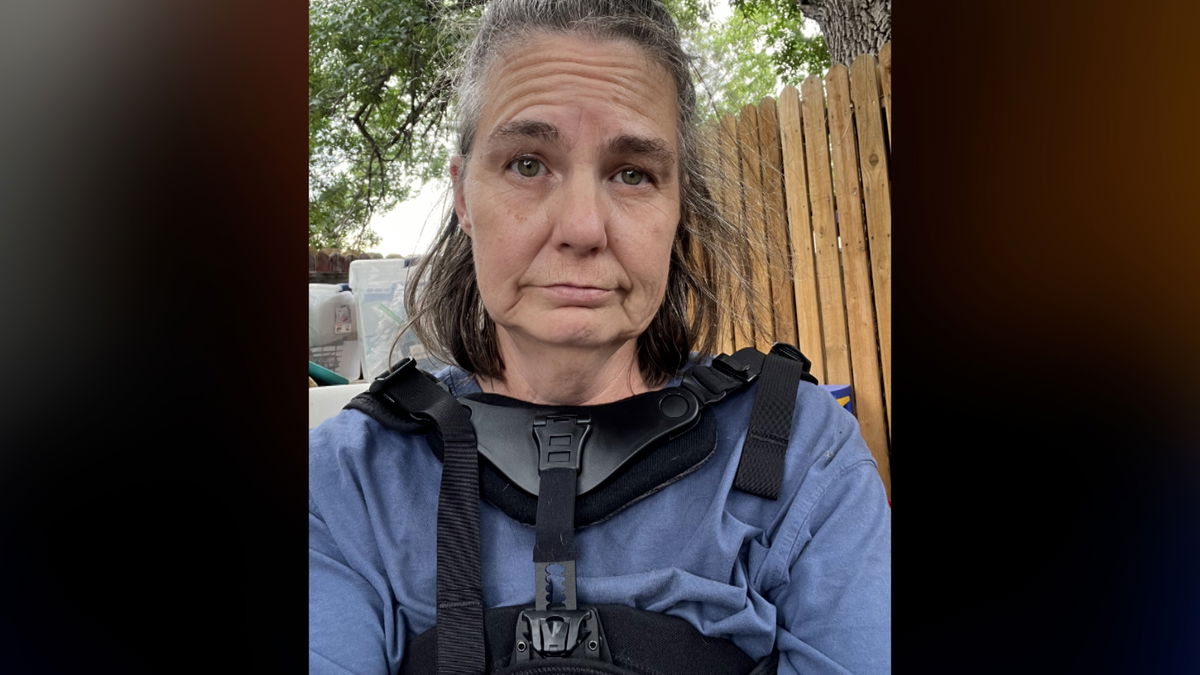

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. (KRDO) - Back on June 22, after fueling up at the Sam’s Club on Woodmen in Colorado Springs, Christine Hyatt had a seizure while waiting to turn south onto Academy.

Luckily, she was at a stop, and the seizure only caused her to roll slowly into the back of a Jeep instead of the middle of the intersection.

“It could have been so much worse, so much worse,” she said while recalling the scenario that day.

Although the collision wasn’t serious, the seizure was so violent that it broke her back in four places, and she spent three days at Penrose Hospital.

Nearly three months later, she is afraid to drive out of fear of what could happen if she suffers another seizure.

She has also had to stop working, which previously required her to walk through large retail stores as part of her job as an independent brand manager.

"I'm dealing with a lot of pain,” she says, “I can't stand for more than a few minutes at a time without the pain overtaking me."

Before she left the hospital, the staff referred her to a neurologist.

However, the earliest she could get an appointment was January 31, 2025, more than seven months later.

She describes the journey to get a neurologist appointment as “a nightmare and a half.”

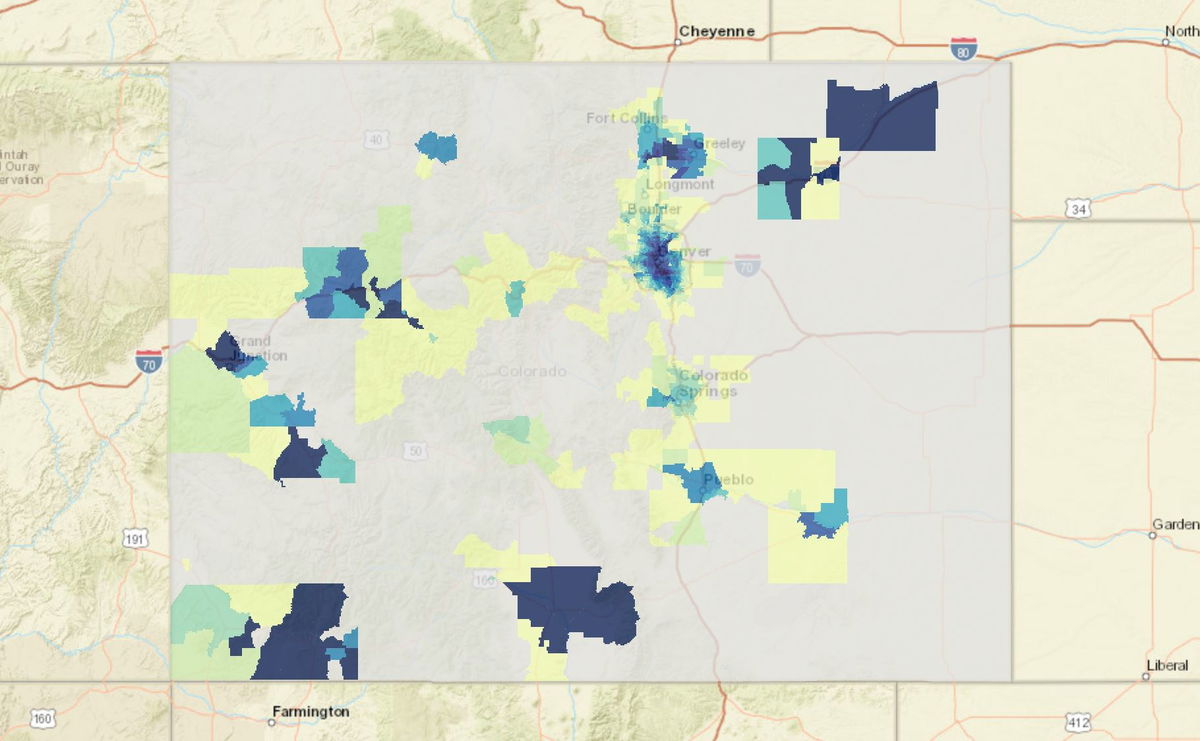

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment tracks the areas of the state with the greatest shortages of access to primary care.

Among major metropolitan areas, only Denver and Grand Junction have areas labeled as a “1”, meaning the shortage is minimal.

Most of Pueblo is labeled a “4”, meaning the supply isn’t as good.

Most of Colorado Springs, however, is only a “6” or a “7”.

Dr. Abigail Urish is a primary care physician and also president of the Colorado Academy of Family Physicians, which represents about 2500 doctors and medical students.

She says although new patients can get into her clinic within a month or so, she has heard of many other scenarios where people wait 4-6 months for primary care.

"It makes me sad. You know, I think we go into primary care because we want to have people have their health problems be addressed in a timely and efficient way so that we don’t get diseases to develop into worsening kinds of states. And it’s hard when we want people to be able to have access and yet there are a lot of barriers that are somewhat out of the control of the physicians that we have because it’s a workforce issue," she says.

Urish believes that Colorado is about average compared to other states when it comes to the supply of physicians, with a ratio of one primary care physician for every 1700 people.

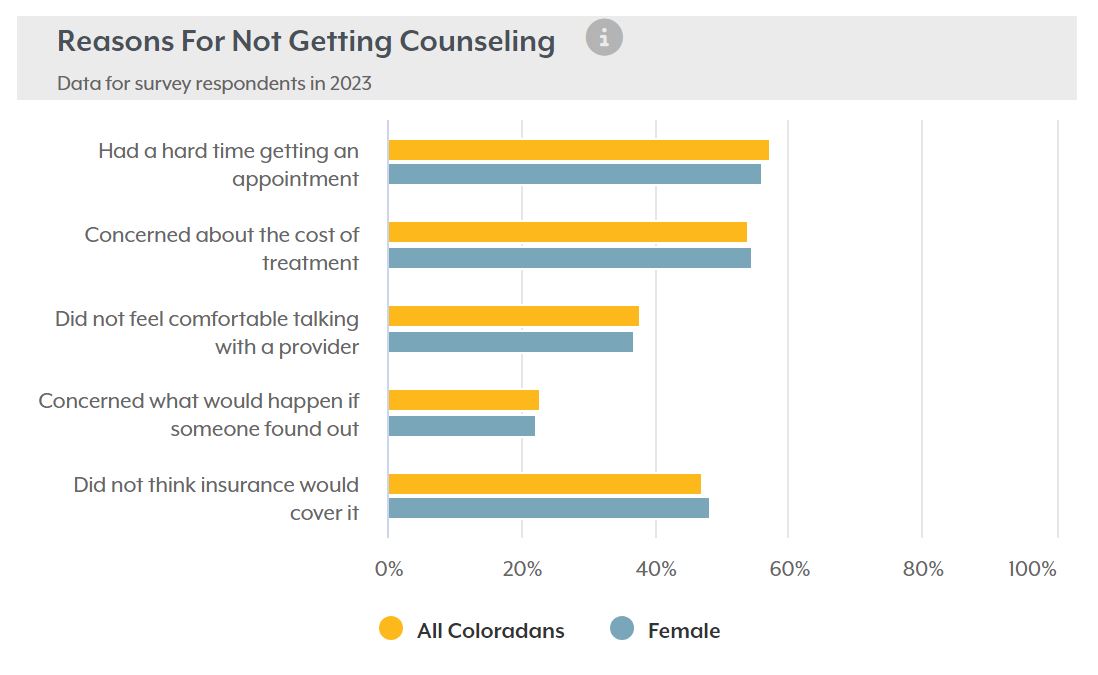

The frustration among patients was apparent in the most recent survey performed by the Colorado Health Institute.

According to the survey, 17% of Coloradans said they could not get the mental health care they needed in 2023, and the most common reason listed was "had a hard time getting an appointment".

HOW DID WE GET HERE?

The shortage of physicians is a result of numerous factors that have all grown in significance over the last few years.

Urish believes there are numerous barriers that prevent young people from going into the medical profession in the first place.

One of those barriers is the cost of attending medical school.

According to data from the Association of American Medical Colleges, the cost of attending a 4-year medical school now ranges from $41,000 per year to $96,000 per year, depending on whether the college is public or private and whether the student is a resident or nonresident.

Urish explained that medical school is typically followed by at least three more years of hands-on residency training that typically pays very little.

"So if people come out of college and go into residency and are making minimum wage or below, based on the number of hours that residents work, it's not very enticing for them to go into primary care, with the outcome being that they're going to make one of the lower salaries within the whole specialty of medicine," she said.

Urish is also concerned about the number of residency programs in Colorado, which is lower than the national average, saying it's an area they are concerned with and keeping an eye on.

Statistics from the University of Colorado Denver’s Anschutz Medical Campus show the number of graduates hasn’t declined, and the overall graduation rate continues to rise.

However, the number of graduates still hasn’t kept up with Colorado's growing and aging population.

According to UCHealth, the largest healthcare system in Colorado, it provided 3.9 million outpatient visits in the 2019 fiscal year.

In the most recent 2024 fiscal year, it provided 8.7 million outpatient visits, an increase of 123%.

During the same period, however, the number of UCHealth physicians only increased by 63%.

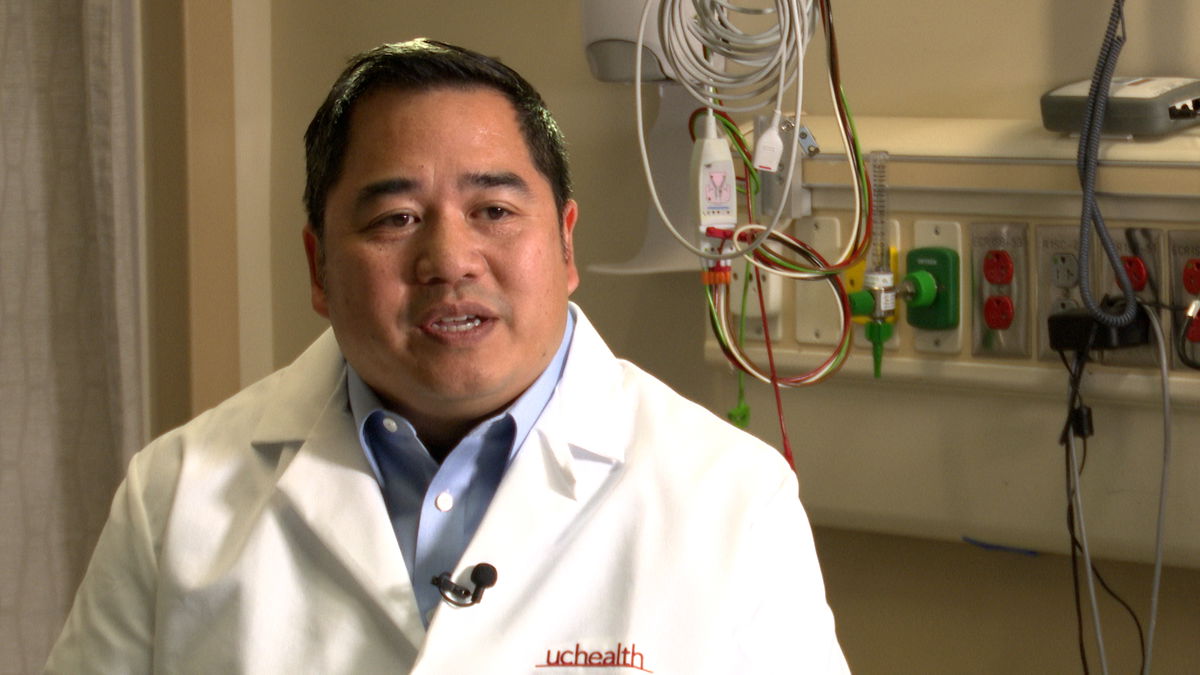

Dr. Robert Lam, an emergency room physician at UCHealth Memorial Central, agrees the growth in Colorado Springs has been a challenge for the medical community to keep up with.

“That growth has been positive in a lot of ways,” he says, “but we haven’t really kept pace with being able to recruit and retain the number of primary care physicians and specialists that we need in our community.”

Lam also recalled studies that showed a third of the healthcare workforce left the industry during the COVID-19 pandemic, although it’s unclear how many physicians were among the workers that left and didn’t return.

He believes another factor contributing to the current shortage and likely to fuel a continuing shortage is the number of doctors leaving the profession due to their age.

“20% of physicians are actually over 65, another 22% are age 55 to 65, so that's almost half the physician workforce that is very close to looking at retirement,” he said.

Along with the lack of new medical school graduates, COVID-19, and the growing medical needs of Colorado’s aging population, Mannat Singh believes a recent wave of consolidation in Colorado and nationwide has made both patient access and affordability more challenging.

Singh is the Executive Director of the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative and says legislators in some states are pushing back.

“We are seeing anecdotally and with evidence that it (consolidation) is limiting patient access and increasing patient costs, and providers including physicians, nurses, and the healthcare workforce, are also then being challenged in being able to provide the care that they want to for their patients.”

Singh says her organization, which advocates on behalf of patients, will continue researching and investigating the impact of the consolidations.

RELATED: Physicians accuse Peak Vists of putting profits ahead of patients

WHAT’S BEING DONE TO ADDRESS THE SHORTAGE?

In April, state lawmakers approved nearly $250 million to expand healthcare programs at higher education institutions.

Much of that will go toward creating a new medical school at the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley.

The College of Osteopathic Medicine at UNC will “position the university to better meet the workforce needs of the state and region” according to the university.

Dr. Urish, however, believes the recruitment needs to start even earlier, and not just in urban areas.

“One of the things that our Colorado Academy of Family Physicians is working on is trying to recruit people from the area where they are from. So in high school, have health care fairs where students can learn about different physician options. Some people don't choose family medicine just because they don't know of all it entails and the wonderful opportunities we have in what I would call the best specialty there is,” she says.

Urish also pointed out a bill that has been introduced and re-introduced in Congress that would allow borrowers in medical or dental internships to defer student loan payments until the completion of their programs.

Currently, those in residency programs are responsible for making loan payments even though they are not being paid anywhere close to the salary of a fully certified physician.

FORCED TO WAIT

Even if Colorado’s third medical school comes online in 2026 as scheduled, it will still take years to inject more physicians into the workforce, providing little help for people like Christine who need help now.

Sadly, she claims the mental stress of not knowing the root cause of the seizure, because she has yet to be evaluated by a specialist, is just as bad as the physical pain she continues to endure.

"I don't know the solution, but there has to be something better than where we're at today. There has to be," she says.

For anyone struggling to find a physician, Dr. Urish recommends checking with their health insurance provider to find out which clinics are in their network, and then going down that list.