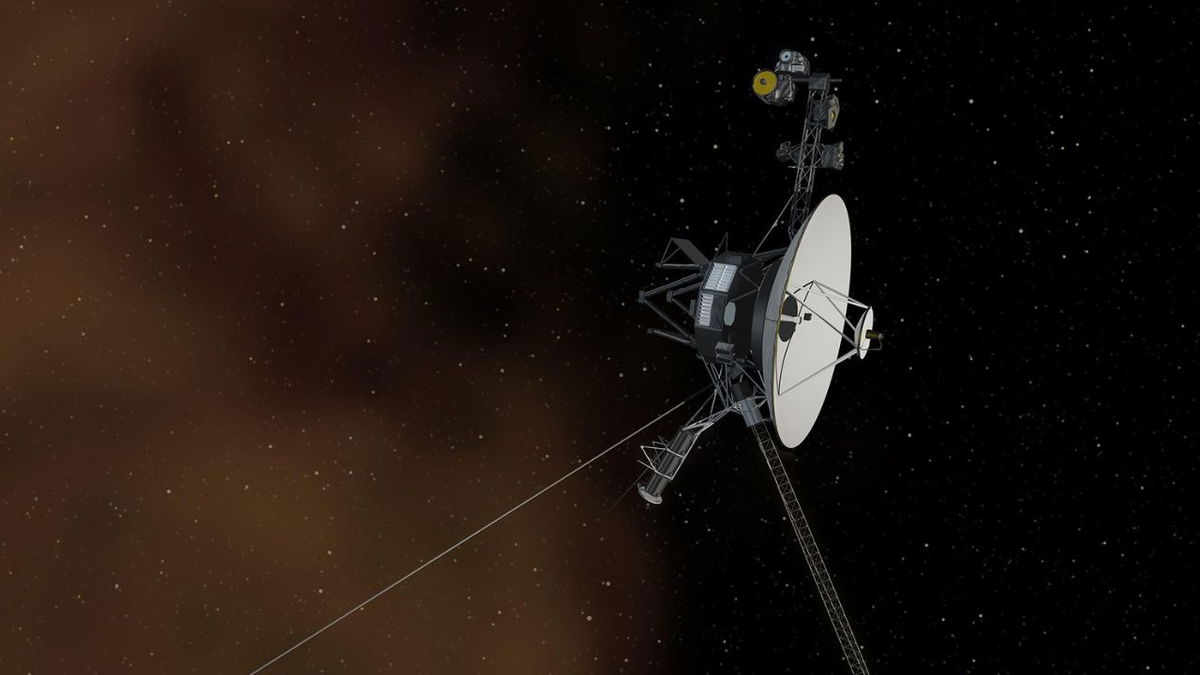

Voyager 1 is back online 15 billion miles away in interstellar space. But the end could be near

By Ashley Strickland, CNN

(CNN) — NASA engineers have successfully restored contact with Voyager 1 and the spacecraft is operating normally after its dwindling power supply caused a weekslong blackout.

The issue began in October when the aging probe automatically switched from its primary X-band radio transmitter and began relying on a much weaker S-band radio transmitter to communicate with its mission team on Earth. The farthest spacecraft from Earth, Voyager 1 is currently exploring uncharted territory about 15.4 billion miles (24.9 billion kilometers) away.

The probe autonomously made the transmitter swap when its computer determined that Voyager I had too little power after the mission team sent a command to turn on one of its heaters.

The unexpected change prevented engineers from being able to receive information about Voyager 1’s status, as well as the scientific data collected by the spacecraft’s instruments, for nearly a month.

After some clever problem-solving, the team was able to switch Voyager 1 back to its X-band radio transmitter and receive its daily stream of data again starting in mid-November.

“The probes were never really designed to be operated like this and the team is learning new things day by day,” said Kareem Badaruddin, Voyager mission manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, in an email. “Thankfully they were able to recover from this issue and learned some things.”

But it’s just one of many challenges the mission team has had to face in recent years as Voyager 1, and its twin probe, Voyager 2, continue to defy the odds and explore space more than 47 years after they lifted off.

Decreasing power, creative solutions

The probes, which launched weeks apart in 1977, have long outlasted their original missions, designed to fly by the largest planets in our solar system over the course of four years.

Now, they’re in interstellar space and the only spacecraft to operate beyond the heliosphere, the sun’s bubble of magnetic fields and particles that extends well beyond the orbit of Pluto.

Both spacecraft are powered by the heat from decaying plutonium that is converted into electricity. Each year, the probes lose about 4 watts of power, according to NASA. That’s equivalent to a small, energy-efficient light bulb.

“We’ve known that power is running out (on board) both Voyagers for some time,” Badaruddin said. “This year it forced the mission to turn off a science instrument on Voyager 2. But these probes have lasted so much longer than anyone anticipated they would, and it’s amazing that we’re squeezing every last bit of power (and science!) out of them.”

The mission team began turning off any systems that weren’t crucial for flying the probes about five years ago. Some of those systems included heaters that were designed to keep the science instruments operating at the correct temperature.

But to their surprise, all the instruments kept working, even at temperatures lower than those at which they had been tested decades before.

Occasionally, engineers send commands to Voyager 1 to turn on some of its heaters and warm components that have sustained radiation damage over the decades, Bruce Waggoner, the Voyager mission assurance manager, told CNN in November. Heat can help reverse the radiation damage, which degrades the performance of the spacecraft’s components, he said.

But the command sent to the heater on October 16 triggered the spacecraft’s autonomous fault protection system. If the spacecraft draws more power than it should, the fault protection system automatically shuts off systems that aren’t essential to conserve energy. The team discovered the latest issue when it couldn’t detect a response signal from the spacecraft on October 18.

Given that the Voyager probes have already shut off all of their nonessential systems except for science instruments, the fault protection system shut off the X-band transmitter and switched to the S-band transmitter because the latter uses less power.

Voyager 1 has been using the X-band transmitter for decades, but the S-band hadn’t been employed since 1981 because its signal is much fainter than the X-band’s. The team had to seek out the faint S-band signal before they could restore reliable communication with the spacecraft.

The mission team successfully commanded Voyager 1 to revert to the X-band transmitter on November 7 and began collecting science data the week of November 18, and they are actively resetting the system used to synchronize Voyager’s three computers. This is one of the last tasks to make sure Voyager is back to how it was before the transmitter issue.

This transmitter switch is just one of several innovative hacks NASA has used to overcome communication challenges with the long-lived mission this year, including firing up old thrusters to keep Voyager 1’s antenna pointed at Earth and coming up with a solution for a computer glitch that silenced the probe’s stream of science data to Earth for months.

Keeping the Voyager probes online

The Voyager team has computer models to help them predict how much power the spacecraft’s heaters and instruments are expected to use. But the fact that turning on one heater triggered the fault protection system is a signal to the team that the probe’s future is more uncertain than they realized.

“This implies that the virtual model that the team uses to calculate how much power is available (and thus how many systems/instruments can be operated) has uncertainties and/or is incomplete at the level that the mission is currently working at, which often involves a margin of less than a watt,” Badaruddin said. “There used to be a small reservoir of power available for situations like this, but earlier this year the team opted to use that reservoir to keep science instruments going longer.”

The Voyager probes started out with 10 science instruments each. Certain instruments were shut off on Voyager 1 in 1990 to conserve energy because those tools were no longer needed after the spacecraft completed its flybys of Jupiter and Saturn.

Now, just four instruments operate on each spacecraft, and they are used to study charged gas called plasma, magnetic fields and particles in interstellar space, and the Voyager probes are the only spacecraft studying this uncharted territory.

Voyager 1 and its twin send back science data continuously through the Deep Space Network, a system of radio antennae on Earth, with about six to eight hours of the probes’ detections returning each day. Data isn’t stored on board, so anything that was sent home by Voyager 1 during the transmitter issue was lost.

“However, the science that Voyager is doing now is really about the big picture and long-term observations, so the team is not too concerned with this drop-out,” Badaruddin said. “The bigger issue is how long can we keep the science instruments going with the current power available.”

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2024 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.