Lower Arkansas Valley farmers warn cities of water loss consequences

OTERO COUNTY, Colo. (KRDO) - There is a battle going on right now across the west between cities and farming communities... over water.

Southeastern Colorado has become a target lately of large thirsty cities, but now many of the folks who live there are voicing concerns about not only the future of their farms but the future of America’s food supply.

The Hanagan family in Otero County is among them.

Kim runs the family’s market along Highway 50 most of the time, where her sons frequently arrive with new shipments, while Eric Hanagan manages the farm a few miles south of Swink.

He is the fifth generation in his family to farm their land, which now includes about a thousand acres.

"We were founded about 1909," he says, “It’s not an easy job, but it's a fun job."

The family’s market sells just about everything that can be grown in the Lower Arkansas Valley, and even a few things like peaches and apples brought in from the Western Slope.

His farm uses water that flows down a ditch that originates from the Arkansas River.

The Lower Arkansas Valley has been called 'The Garden Of Eden' when it comes to growing because the soil is just so fertile.

"I don't really see myself doing anything else,” says Hanagan.

However, he knows that turbulent waters are ahead.

According to the American Farmland Trust, every day in the United States 2,000 acres of farmland are paved over, fragmented, or converted to uses that jeopardize farming.

Much of that conversion is done in order to move the water rights to growing cities, including Colorado Springs.

As a result, the overall amount of food produced in the country has declined.

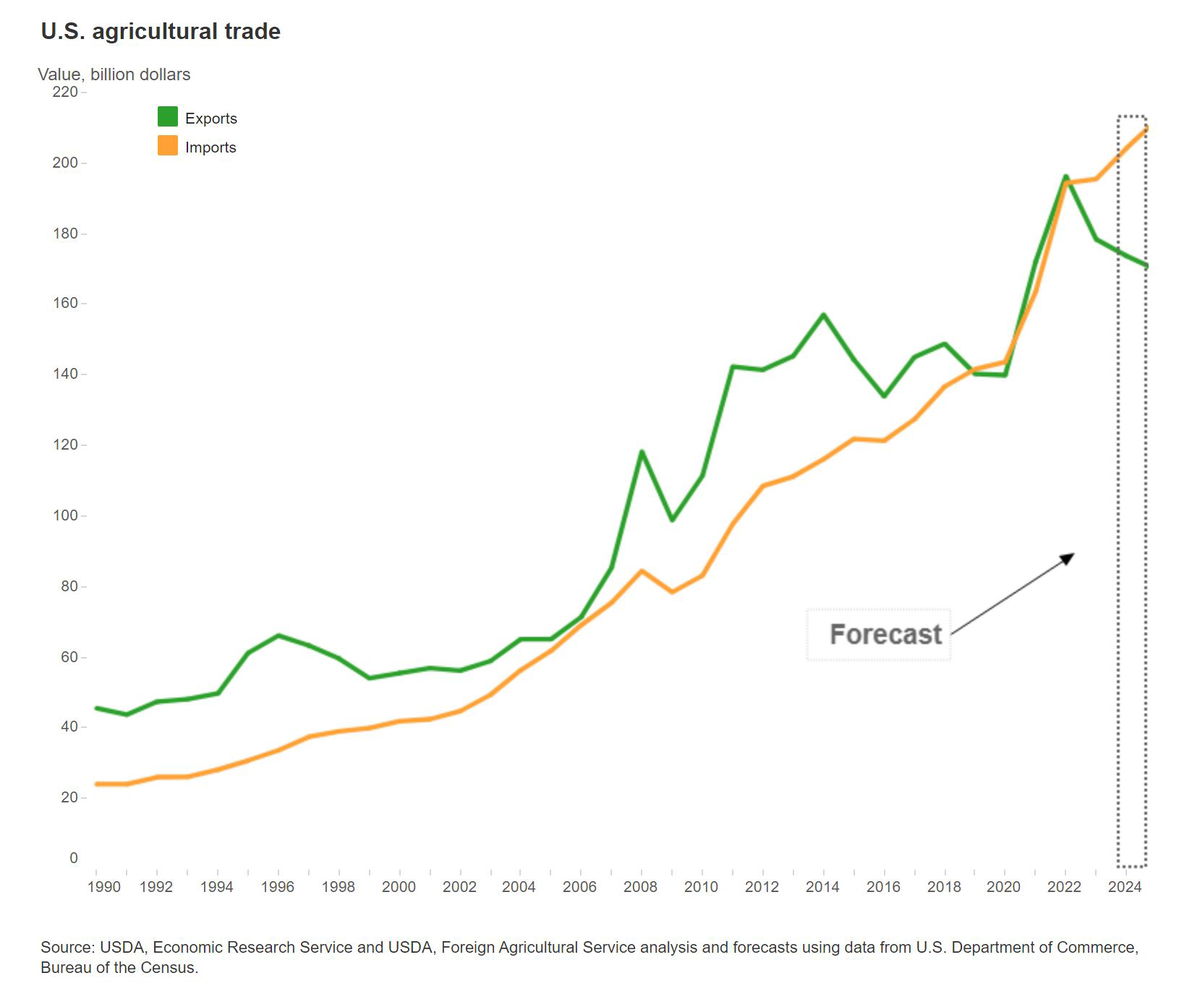

According to data from the US Department of Agriculture, the US has imported more agricultural products than it exported in each of the last three years, and the trend is getting worse.

"If we become dependent on foreign food, they can bring our country to our knees in a heartbeat,” says Hanagan.

It’s an issue that Jack Goble has become very personal for Jack Goble, who is both a rancher himself as well as General Manager of the Lower Arkansas Valley Water Conservancy District.

The LAVWCD represents Pueblo, Otero, Crowley, Bent, and Prowers County, the five counties along the Arkansas River, where agriculture is the foundation of the economy.

"At some point, food security has got to become a concern,” he says.

Goble was among several farmers who addressed the city council in Colorado Springs in July when the council was considering annexing just over 3,000 acres east of Fountain, known as Amara.

The Amara annexation was ultimately killed by a 5-4 vote, partially because of concerns over the amount of water the 10,000 new homes planned would require.

"My primary goal (speaking to city council) was to raise awareness that decisions that they were making directly affect their neighbors in the Lower Arkansas River Valley," he says.

Although Colorado Springs Utilities has identified several ways to increase its capacity to store and deliver water, the Arkansas River is among the more realistic options.

The river currently makes up only about 15% of CSU’s water supply.

Currently, customers of Colorado Springs Utilities use approximately 70,000 acre-feet of water per year.

CSU is capable of supplying 95,000-acre feet per year, a figure referred to as the “Reliably Met Demand”.

The utility estimates that by the year 2070 when the existing city land is completely filled in, it will need approximately 129,000 acre-feet.

That leaves a gap of around 34,000 acre-feet, plus any additional amount that would be required to maintain a required buffer above that year’s actual usage.

Unfortunately, Colorado Springs doesn’t have the best track record in Lower Arkansas Valley.

Back in the 1970s, Colorado Springs Utilities bought lots of land in Crowley County to obtain the water rights, and today that land is lost.

Much of the ground is dry and cracking from the lack of moisture to keep it healthy.

"You had all these little thriving communities that are now no more,” Goble explains, “and the one that's there in Ordway is struggling to stay afloat."

Abby Ortega, General Manager for Planning at Colorado Springs Utilities, is also aware of that history.

"That is something no one wants to repeat," she says.

Ortega says the days of “buy and dry” land purchases at CSU are over.

Instead, she says CSU wants to partner with farmers along the river.

CSU is offering to pay for a farmer to install something called a center pivot sprinkler system, which uses far less water than the traditional flood irrigation method.

The average cost of one of these systems for the average piece of land is around a million dollars.

In exchange, CSU obtains the rights to the water on the "corners" of the property, which are no longer irrigated because they can't be reached by the center pivot systems.

The corners usually account for about 20% of the overall property, however CSU believes the remaining 80% can grow the same amount of crops as before because the density of the crops can be higher with the more efficient center pivot system.

Ortega believes it’s a way for both sides to improve their situations.

"We recognize the impacts of water supply development to the Arkansas River Valley and to the farmers there, which is why we're working so hard to partner with them and not drying up farms,” she says.

In addition, Ortega points out that farmers who make the switch shouldn’t suffer any loss of income from it.

“Their production values aren't changing,” she explains, “some of them are actually seeing increased values."

In the first two water-sharing agreements with farmers, the contracts allowed CSU to lease additional water from the farm for 3 out of 10 years, as part of a broader water leasing project with the Fort Lyon Canal Company. The lease could be exercised only through an approved program by the Fort Lyon Canal Company.

However, this provision to lease additional water, a major sticking point for landowners, is no longer included in later agreements.

Along with paying to upgrade sprinkler systems, CSU is also working with farmers to try growing new crops like cotton and sunflowers, which require less water than traditional crops like wheat or alfalfa.

Eric Hanagan believes the two sides can co-exist.

“I'm an optimist," he says.

However, neither he nor Goble are entirely sold on CSU’s proposal yet, and they will continue fiercely defending their livelihoods.

“We have an obligation to keep our valley together. Otherwise, we will die,” says Hanagan.

“At what point are we going to get where we say 'That's enough water, let's leave the rest in farming' and coexist?" Goble adds.