A Colorado Dreamer shares his story as the future of DACA remains in limbo

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. (KRDO) – A federal program meant to protect immigrants who came to the United States as children is up in the air, leaving the lives of millions in limbo.

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, known as DACA, protects those without legal immigration status from being deported. It also allows those recipients, known as "Dreamers," to work, get driver's licenses social security numbers, and receive financial aid for education in the U.S.

The DACA program allows recipients to renew their request to remain in the program every two years and, in some cases, apply for a green card. However, it’s not a path to citizenship.

In the meantime, no new DACA applications are being approved and the roughly two million Dreamers that have been allowed to remain in the U.S. still face an uncertain future.

Related Story: DACA in jeopardy as federal judge considers lawsuit calling for the program's end

KRDO interviewed a DACA recipient from Guatemala who has built his life through the Dream Act. We’re sharing his story and how ending the DACA program could destroy everything he’s worked hard for.

"For us, it’s really a family story of immigration my parents moved here because my grandfather was very involved politically and was an activist and really came to concern for his life," said Mario Hernandez, DACA recipient.

The journey started with Hernandez's grandparents back in the late 60s. His grandpa was a civil rights activist in Guatemala City.

"In Central America, unfortunately, when you're an activist and fighting for rights your life is often in danger," explained Hernandez.

This is why in the early 70s, Hernandez said his grandparents knew they had to get out. They applied for and received a green card to come to the U.S. legally. They eventually settled in Colorado where they found work as an elementary school teacher and had Hernandez’s mother. As a teen, his mother made the decision to turn over her green card to the U.S. Embassy and returned to Guatemala.

Years later, Hernandez’s mother fell in love and had two boys in Guatemala.

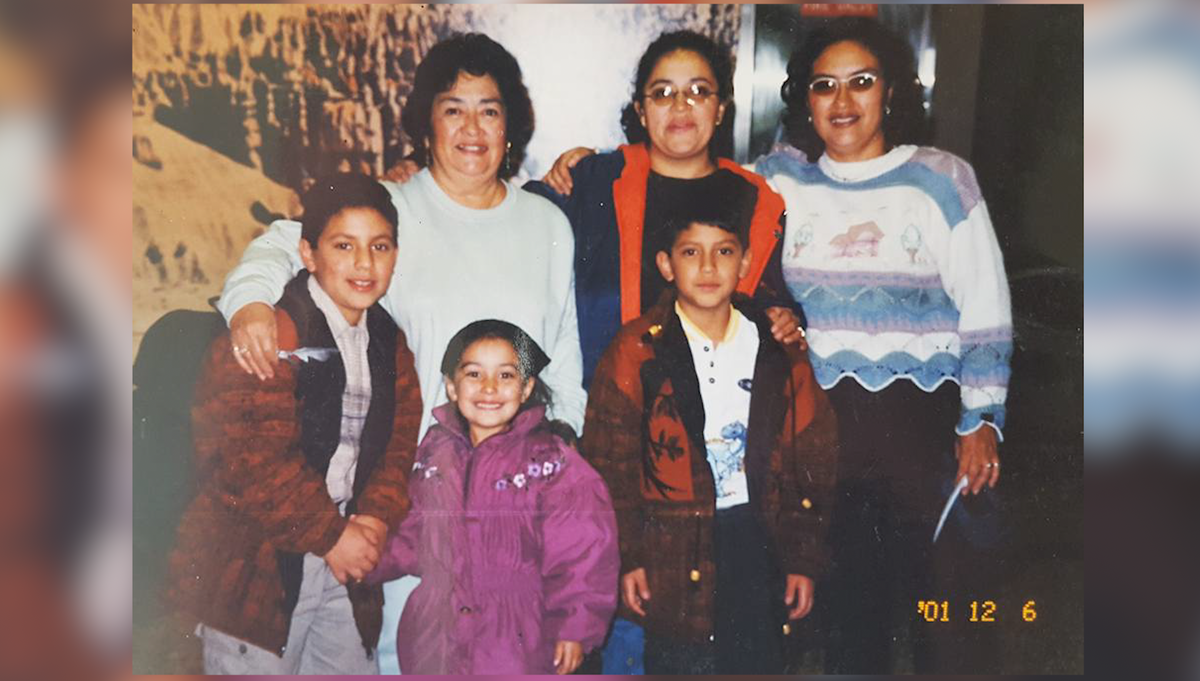

In 2001, his mother was granted a visa and returned to Colorado when Hernandez was 11 years old and his brother nine. The kids came to the U.S. on tourist visas.

"For my mom and I it was always about my brother and I having an opportunity to live in the United States to get a better education and really just to be closer to her parents and my grandparents," added Hernandez.

However, coming to America and speaking no English was their first big challenge.

"Finished fifth grade here and then went on to middle school and very early on I was in the ESL programs, so really focusing on learning English the first couple of years," said Hernandez.

After about three years Hernandez went from not speaking English to being accepted into the International Baccalaureate (IB) Program, an accelerated curriculum for advanced learners.

"Very early on I had aspirations of going to college. That's what the focus of the program is to get you to get some college credits and by the time you graduate from high school and then make it to college," said Hernandez.

It was around that time when Hernandez learned his tourist visa had expired and he was now considered an undocumented immigrant.

"Just to hear my friends to be able to start driving, start learning how to drive. I often had to come up with lies as to why I didn't want to drive,” explained Hernandez. “I would say it's not important to me or I don't want to drive or you know I don't need to.”

"I couldn't work at the time either, I think that was kind of the next level that summer my friends would start getting jobs. They would work at water world or Elitches here and that was a fun opportunity for them, and I would hear stories, but I also didn't have this additional income that was starting to come in to do the fun things that they wanted to do."

In 2009, Hernandez received his high school diploma from Thornton High School. He had been accepted to several colleges in the state and decided on the University of Northern Colorado.

“But, because I wasn’t a documented student, I was actually being charged out-of-state tuition,” said Hernandez.

Hernandez was able to receive some scholarship money for his outstanding academic achievements. Still, covering the rest of his tuition was not easy because Hernandez could not get a work permit. Instead, he was employed by the college under a scholarship program

"It allowed me to attend school for the first three years, but I wasn't able to work and DACA wasn't around until right before I was close to graduation actually," explained Hernandez.

In 2012, just one year before his college graduation, the DACA program was enacted. Hernandez took a chance and applied.

“I was hesitant, it was this new program that I knew also was not going through Congress, it had actually been an Executive Order, so I knew the challenges and what that could mean, and that it could end at any point,” said Hernandez.

After eight months Hernandez was approved for DACA. About the same time he received a job offer as a hall director at UNC.

"To know I can call that job and say ‘I’m taking this job,’ I am excited, I have a work permit,” said Hernandez.

In the last 11 years, Hernandez has received a Master of Business Administration from the University of Colorado in Denver. He is now a business operations manager for Smart Sheets- a software service program.

Hernandez explained he knows other DACA recipients who went on to have careers that allow them to give back to the community and help new Dreamers.

"There is a lot of us that became teachers that work in education that's also contributing to society in a whole new wave and now for DACA recipients that are growing their own families," said Hernandez.

However, if the DACA program ends, he could lose everything.

Hernandez is one of the two million Dreamers who still don't know what their future holds as the legality of DACA is held up in court.

“When I’m thinking about career goals and what I want for myself I would love to buy a home and save enough money to do that, and to really establish myself here,” said Hernandez. “Home in Colorado where I grew up and what I consider to be home.”