A Water Crisis: CSU accelerates projects in response to dwindling river

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. (KRDO) -- Cities across Colorado and throughout the western half of the country are scrambling to secure enough water for their future growth.

The Colorado River currently serves 40 million people, but less rain, less snow, and warmer temperatures have combined to create an unbalanced equation, with demand now far exceeding supply.

At a home near the University of Colorado in Colorado Springs, Top Notch Turf was hired to xeriscape the outdoor space, replacing the traditional sod with rocks and artificial grass.

Nick Byard owns the company and says 2020 was his busiest year yet.

“Last year we put 220,000 square feet down," he says.

Along with much less maintenance, Byard says the biggest reason for xeriscaping is a much smaller water bill. At most homes in Colorado Springs, lawn watering accounts for approximately 40% of the overall water usage. Before watering restrictions were put in place, it was closer to 60%.

Despite massive growth in Colorado Springs over the last few decades, the amount of water used every year citywide really hasn't changed.

Xeriscaping, water restrictions, and new federal requirements for more water-efficient fixtures and appliances have all kept the usage low.

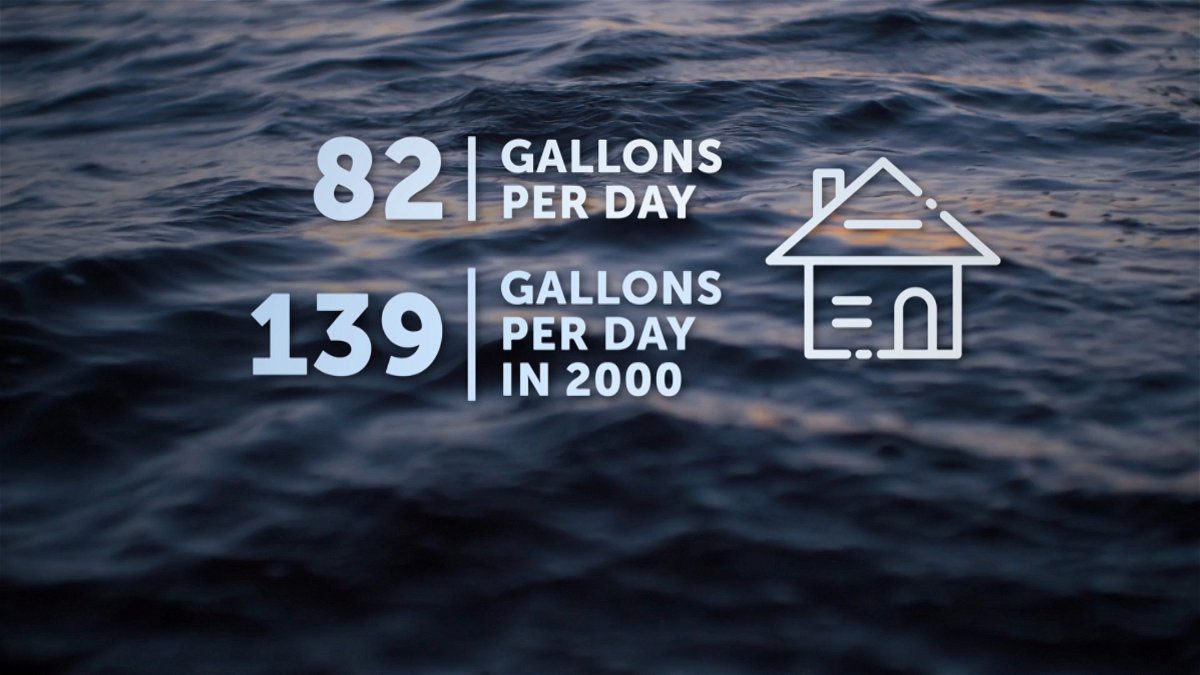

According to Colorado Springs Utilities, the average household in town currently uses 82 gallons per day, 41% less than the 139 gallons used by the average household in 2000.

"We're using roughly the same amount of water that we did in the mid-1980s, even though our population has grown by almost 80%,” says Patrick Wells, CSU’s General Manager for Water Resources and Demand Management.

Wells oversees the 25 CSU reservoirs that are scattered across the state. They include alpine lakes in the high country near Breckenridge, as well as others closer to the city like North Catamount Reservoir on Pikes Peak.

Most of these lakes are not filled with water from rain or snowmelt in the immediate surrounding area.

Instead, 70% of CSU's water comes from the Colorado River Basin, melted snow that's then pumped through a series of pipelines.

CSU has the capacity to store enough water to supply the city for three years. Currently, the reservoirs are about 90 percent full.

Unfortunately, the Colorado River is fading faster than ever. Twenty-two years of drought combined with population growth throughout the west has left Lake Mead in Nevada, Lake Powell in Utah, even Blue Mesa Reservoir outside Gunnison at record low levels.

Lakepedia created a webpage earlier this year with before-and-after images of lakes up and down the Colorado River. Move the slider over each lake to see the difference. This is Blue Mesa Reservoir in Gunnison County:

“We just can't afford to lose more water from the Colorado River,” says Mark Squillace, a professor of natural resources at CU-Boulder.

Squillace says despite the ongoing megadrought, cities including Denver and Colorado Springs are still hoping for more water.

“We're in dire straits with respect to the Colorado River System,” he explains, “and when a big city like Denver says they want to take more water out of that system, I think someone needs to tell them that the time has passed.”

Wells acknowledges that the dynamics have changed in light of the Colorado River crisis.

“We are heading into a period with more uncertainty, with a lot of challenges,” he says.

The diminishing flow along the river isn’t the only factor CSU is closely watching.

The rate of population growth in Colorado Springs has also exceeded what was forecast by CSU planners, forcing CSU to fast forward some of its future strategies.

“That causes us to re-evaluate our planning, and to basically accelerate some projects,” Wells explains.

Those projects include a water-sharing plan with farmers along the Arkansas River, increasing CSU’s water storage capacity, and more aggressive conservation measures.

However, Wells made it clear that CSU is far from running out of water.

“We're in good shape, and we've identified the risks, and we're aware of the risks, and planning for those risks, and I think the future will be bright.

CSU's Integrated Water Resource Plan goes into detail about what future projects are in the works to increase capacity and what factors are used to predict future usage.

For now, CSU isn't asking homeowners to trade in their grass for rock or turf like many cities downstream like Las Vegas already have, but they hope everyone is conscious of the current water crisis, and trying to stretch every drop.

Earlier this year, KRDO reported on the City of Fountain turning down large housing developments because there just wasn't enough treated water available to provide those homes, or enough room to store it before it’s delivered.

Utilities Director Dan Blankenship says Fountain is still allowing homes to be built in smaller numbers, while working with surrounding water providers to secure enough treated water to accommodate all the growth.

Click here for Part 1 of our series on the Colorado River, which focuses on the role agriculture plays in the big picture.